Newsletter Issue 20 - October, 2010

In this issue:

Ask Dr. Copyright - duration of

a copyright

Famous trademarks

Does a food trademarks protect the recipe?

Patent search tool for FireFox

PTO issues patents, reduces backlog

Ask

Dr. Copyright...

Ask

Dr. Copyright...

Dear Dr. ©:

How long does a copyright last? I seem to remember that it's 28 years or so, but that it can be renewed, and that's why they sing cheesy "faux" happy birthday songs in restaurants... because they don't want to have to pay the two little old ladies who own the rights. Right???

signed,

Wanting to sing the REAL song to my kid.

Dear Wanting:

Like any good urban legend, there is a kernel of truth (or maybe a general) in what you've written. Most of it, however, is wrong. You see, when copyright laws were first enacted in the early history of our country, copyrights lasted 14 years, and if the author survived those years, he or she could renew the registration for an additional 14 years. In fact, this "term" was directly inherited from the English law, where, under the Statute of Anne (1710) the term was the same. The term was lengthened by Congress in 1831 to 28 years, plus a 14 year renewal, and in 1909, the renewal term was doubled to 28 years, giving 56 years of protection to registered works. Then, beginning in the 1970s, Congress started tacking on years, until finally, in 1998, we got the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (sometimes called the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act") that stretched copyright to the life of the author plus another 70 years (and for corporate and anonymous works, a flat 95 years.) Any work written by an author who died before 1940 may now be in the "public domain", but then again, if that author worked for a corporation or published the work anonymously, it may still be protected, unless it was published before 1905.

Now for the really bad news: even if you know that the work is still protected by copyright, there is no registration system that is kept up to date, so you may never be able to find the person or company that owns the copyright, even if you wanted to pay for the right to use the work! These are called "orphan copyrights" and they really make the job of "rights clearance" a nightmare.

Why is the copyright system such a mess, you might ask? Because simply put, major corporations, like Disney, want to continue to control valuable properties, like Mickey Mouse. In 1998, when the copyright on Steamboat Willie was about to expire, Disney supported legislation that extended all copyrights to the present terms. That's why.

If you think that this situation is bad, I have news for you...it gets worse.

Now, about "Happy Birthday"... the melody for Happy Birthday was written by Mildred J. Hill and Patty Smith Hill. The song was called Good Morning to All and was first published in 1893 in the book Song Stories for the Kindergarten. The melody has since passed into the public domain. Jessica Hill (another Hill sister) was able secure the copyright to the song with those clever lyrics in 1935. That original copyright should have expired in 1991, but because of all that Congress and Disney has done for copyrights, Happy Birthday is now not due to expire until at least 2030.

Through a chain of corporate purchases, the copyright for Happy Birthday To You is now owned by Time Warner company. Happy Birthday's copyright is licensed and enforced by ASCAP, and the song brings in more than USD $2 million in annual royalties. Under the Copyright Statute, you can sing the song at home to your kids, but any public performance must be paid for with a royalty - not to the little old ladies, but to a major media corporation.

So the Doc's advice? Stick with the cheesy restaurant happy birthday songs. You'll be sticking it to the Man as well.

Any other questions about copyright? Just ask an attorney at

LW&H. They find this stuff fascinating.

Lawrence Husick

Would You Believe that the Classic Shape of the Cobra 427 S/C Lacks Distinctiveness?

I took my Cobra down to the track,

hitched to the back of my Cadillac,

Everyone was there just a waiting for me

There were plenty of Stingrays and XKEs...

(written by Carol Conner)

The Rip-Chords - 1964

It's just a shame that, according to the U.S. Trademark Trial and Appeal Board ("Board"), your 1965 Cobra 427, the one you recently purchased for just $800,000, has not acquired distinctiveness -- at least not for trademark purposes. Here's why. In 1999, the Carroll Hall Shelby Trust ("Shelby") filed a trademark application to register the "distinctive" shape of the Cobra 427 S/C vehicle. Upon publication, in November 2001, the application was immediately opposed by Factory Five Racing, Inc. ("Factory Five") on several grounds, the most important being that the Shelby design had not acquired distinctiveness.

A little background is in order. In the early 1960s, Shelby partnered with Ford to produce high performance sports cars under the "Cobra" brand. Although Cobra production ceased in 1968, numerous third parties started producing Cobra replica kits, including the Cobra 427 S/C. This was despite Shelby's attempts at stopping them. Then, in the early 1990s, presumably under the theory that if you can't beat em, join em, Shelby released its own so-called "continuation" models, also in the form of kits. The question before the Board was whether purchasers of kits recognized Shelby as the source of their vehicles, in which case the trademark would issue, or whether the design lacked acquired distinctiveness, meaning that Factory Five would prevail in its opposition.

The Board determined that its analysis was not dependent upon the resale value or popularity of the original Cobra production models. Nor was it persuaded by Shelby referring to his own kits as "continuations" of the original production models. More important was that Shelby's own kits were not heavily marketed; since the 1970s, nearly 200 other parties had marketed Cobra kits despite Shelby's attempts at selling some of them licenses. The Board noted that more unauthorized third-party replica kits have been sold over the years than either the original Cobras or authorized replicas. One web site cited by the Board stated that "The Cobra became the most replicated design in automotive history with literally hundreds of companies capitalizing on the popularity of the design." The New York Times wrote in 2009 that "The car's [Cobra's] history has fueled an industry that makes relatively low-cost Cobra replicas." Shelby's own enforcement efforts were at best paltry and unconvincing. Shelby's most important evidence, a customer survey performed by its expert, was rejected by the Board as ambiguous and lacking reliability. The expert wasn't even sure that the picture of the Cobra used with survey was that of the car at issue in the opposition action.

So Shelby had a long row to hoe. Well-established law provides

that "configurations of products are not inherently distinctive and

may only be registered as marks upon a showing of acquired

distinctiveness." (Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros, Inc. 529 US

205). To establish acquired distinctiveness, the trademark applicant

must show -- by direct or circumstantial evidence -- that the

primary significance of the product configuration in the minds of

consumers is not the product but the source of that product. The

Board concluded that Shelby's circumstantial evidence that kit

purchasers perceived Shelby as the source of their kits was weak and

that his direct evidence -- the survey results -- was flawed and "of

little or no probative value." The Board sustained Factory Five's

opposition and held that Shelby failed to meet his burden of proof

that the Shelby design mark had acquired distinctiveness. This case

underlines the importance of policing your marks and obtaining

reliable experts when its your turn to defend your mark.

Adam Garson

Barkeep, I'll have an IP Cocktail with a Twist!

Say it's a warm day and you've popped into the local tiki-themed

cocktail lounge for a refreshing beverage. Is it possible that the

tiny umbrella-embellished cocktail youíve just been served is an

infringement of someone else's intellectual property rights?

lounge for a refreshing beverage. Is it possible that the

tiny umbrella-embellished cocktail youíve just been served is an

infringement of someone else's intellectual property rights?

Take the case of Pusser's Rum Ltd., a rum distiller located in the British Virgin Islands. Pusser's owns a registered USPTO trademark for the PAINKILLER, an alcoholic fruit drink made with fruit juices, cream of coconut and coconut juice. About the same time, a cocktail lounge called Painkiller opened in New York City with a signature cocktail consisting of rum -- not Prusser's rum. A representative of Pusser's threatened the lounge owners with a cease and desist order.

Another company, Gosling's Export, a family owned Bermudan distiller since 1806, owns four registered trademarks for it's signature drink consisting of Gosling's Black Seal rum and ginger beer called the "Dark 'n Stormy. The New York Times recently reported, that Gosling's aggressively pursues bars, restaurants and other rum makers from selling or advertising drink recipes called the "DARK 'N STORMY but using rum other than Gosling's own.

Although companies like Pusser's and Gosling's appear to have legitimate gripes, neither truly understand its intellectual property rights (or they're just bullies). Although trademarks are certainly protectable, recipes (i.e., particular mixtures of ingredients) typically are not. If a drink recipe is published, copyright may protect the manner in which the recipe is expressed, but not the recipe itself.

In the case of Pusser's Rum, it owns rights in a registered Trademark -- PAINKILLER -- for a bottled alcoholic beverage concoction sold in establishments and liquor stores, not a drink recipe. Pusser's may have the right to stop others from bottling the particular ingredients and selling them to others as PAINKILLER, it has no right to stop others from using the recipe.

Likewise, the four trademarks registered by Gosling's are for

marketed products (premixed or cocktail kits) and bar services.

Goslings owns no trademarks for drink recipes. So feel free to grab

your ceramic tiki mug and mix up a tropical cocktail of rum, fruit

juices, coconut cream and juice and call it whatever you want (just

don't sell it under someone else's trademark).

Deborah Logan

New Patent Search Tool For the Firefox Browser

On-line patent searching has profoundly improved the patent system. An inventor can use free Internet resources to search for patents and published applications relevant to his or her invention. The mother of all free on-line patent databases is that of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). The PTO database has the advantage that it is complete and has the disadvantage that it is not user-friendly. The competing Google Patent Search tool is very user friendly and also free, but is not complete.

Users of the Firefox web browser have a powerful new screening and download tool to access the PTO database. The Aspator extension for Firefox allows rapid screening of many patents found during a search by allowing the inventor quickly to select among the abstract, the first claim, all the claims, and the first three drawings for an initial screening review. If the screening review finds a patent that is relevant, the inventor can download the entire patent as a .pdf file and view, save or print the patent directly from Google Patent Search, the European Patent Office, or the Aspator servers. The Aspator server download appears to be buggy, but the other features work well.

The Aspator extension for Firefox is shareware with a requested

donation of $3.88. We recommend that you check it out.

Robert Yarbrough

PTO issues more patents, reduces backlog

The backlog of pending patent applications at the PTO is

important to inventors because a large backlog results in long wait

times before a patent application is reviewed by an examiner. During

the last years of the last administration, the backlog at the PTO

grew so large that the average time to first office action was over

29 months from the filing date of a patent application. The

administration of David Kappos at the PTO is implementing a number

of programs to enhance productivity and reduce the backlog. In just

one year, the average time to the first office action from the

initial filing has dropped to 25.7 months, and still is going down.

because a large backlog results in long wait

times before a patent application is reviewed by an examiner. During

the last years of the last administration, the backlog at the PTO

grew so large that the average time to first office action was over

29 months from the filing date of a patent application. The

administration of David Kappos at the PTO is implementing a number

of programs to enhance productivity and reduce the backlog. In just

one year, the average time to the first office action from the

initial filing has dropped to 25.7 months, and still is going down.

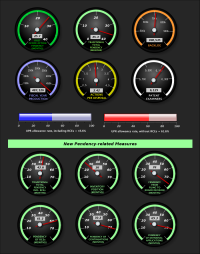

One of those programs is the "Patents Dashboard," which is an

easy-to-understand representation of PTO management performance. The

Patents Dashboard presents a visual representation of changes in the

number of examiners, the backlog, the average pendency and other

metrics. We can attest that things are moving quicker at the PTO. We

recently received a first office action on the merits of a utility

patent application within 5.5 months after filing the original

application, with claims allowed, which has to be a record.

Robert Yarbrough